Social License in Action

CASE HISTORY – MINERA SAN CRISTOBAL

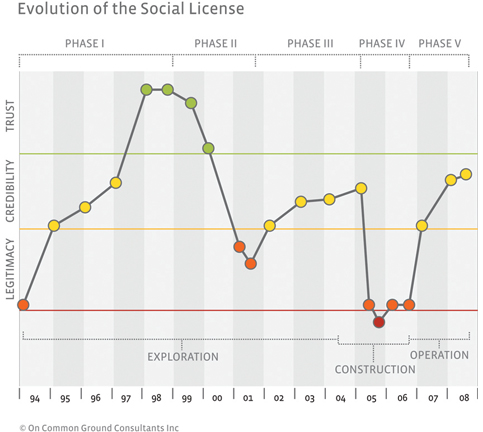

The best way to illustrate the nature of the Social License is through a case history. The graph below provides a pictorial representation of the quality of the Social License for the San Cristobal Project in terms of community perceptions of legitimacy and credibility and the presence of trust over a fourteen year time period from 1994 to 2008. Permission to publish this information was granted in September 2008 by Apex Silver, majority owner and operator of the mine at that time. The information has been presented in a peer reviewed publication and at a number of conferences.

Today, San Cristobal is a large zinc, lead, and silver mine in the southern Altiplano of Bolivia operated by Minera San Cristobal (MSC), which is 100% owned Sumitomo Corporation. The quality of the consolidated Social License given by the two host communities to the project San Cristobal (on who’s lands the ore body is located) and Culpina K (where the water supply and tailing facility are situated) was estimated first using historical documents and the experience of persons who had been present throughout the life of the project using a basket of indicators, then verified through interviews with community members and adjustments made where necessary based on the perspective from the community.

Minera San Cristobal: The evolution of the Social License to Operate

As illustrated in the graph, the quality of the relationship has been dynamic, changing over time in response to various factors, which may be summarized as follows:

Phase I – 1994 – 1998: Gaining the Social License

- In early 1994, rights to the mining concession are acquired by Mintec which, together with permission from the community to access the surface, establishes formal, legal status and ability to start work on the ground. The company rapidly builds social legitimacy with the local community by providing information and employment.

- By March, 1995, geological indicators of widespread mineralization are identified. Mintec steps up a dialogue with the community and provides additional benefits. Social and environmental baseline studies for an environmental impact assessment are initiated.

- In early 1997, there are clear indications of a very large mineral system are demonstrated through drilling. Mintec believes that a mine can be developed in the near future. Accordingly, the company begins a process of consultation with the community of San Cristobal to relocate the population away from the mineral deposit. Mintec empowers the community to manage essential aspects of the relocation such as selection of the new town site, design of houses and infrastructure, eligibility and benefit package. The community comes to feel that they are partners (co-owners) in the project – Mintec has the mineral deposit, but the community has given its land to make a mine possible. Negotiations begin with the sister community of Culpina K for land for the tailings facility.

- In June, 1998, a comprehensive resettlement agreement is signed with the San Cristobal community. A land purchase agreement is reached with Culpina K. Trust reaches an all time high.

- In November, 1998, the community of San Cristobal is relocated to the new town site together with the colonial church and cemetery.

Phase II – 1999 – 2001: Problems in the Relationship

- Through 1999, the women, who were largely excluded from the negotiations and planning for the relocation, voice complaints about the houses; ‘they are not what we wanted’. Culpina K residents start to think that they have made a bad deal.

- At the end of 1999, the project is sold to MSC. Trust is eroded because the company has failed to deliver on commitments made in the resettlement agreement. Further, although the company has obtained necessary permits to construct and operate a mine, there are now doubts as to the feasibility of the project and the company has drastically reduced the number of employees.

- Early in 2001, the project fails feasibility because of low metal prices. MSC close all field operations. The communities are frustrated and trust is lost. Contacts between the company and the communities become infrequent. The company remains non-compliant with the terms of the resettlement agreement. Credibility is lost. The project remains legitimate in the minds of community members because they want the employment and better future they hope it will bring.

Phase III – 2001 - 2004: Regaining Credibility

- Realizing the need to stabilize and strengthen the relationship with the community, the company initiates a program of assistance late in 2001, with employment for local people, designed to assist agriculture and tourism. Credibility is restored with delivery of the programs.

- A highly innovative program to encourage tourism is launched in 2002. Culpina K becomes deeply involved, San Cristobal less so because it would rather have the mine.

- In 2004, an upturn in market conditions renders the project feasible and MSC announces the start of construction. Credibility peaks as the communities welcome the construction of ‘their’ mine and the potential for employment during construction.

Phase IV – 2004 – 2006: The Chaos of Construction

- In mid 2004, new company management who has no knowledge of the social history of the commitments to the communities is installed to supervise construction. Contact between the company and the communities breaks down as the company drops meetings with the communities that involve top management. The communities feel deserted, disenfranchised because of a perception that they are not being respected, and commitments for employment and training are not being honored. Credibility is lost almost immediately. Despite employment for almost all local people, social legitimacy quickly drains away as the communities feel they have been overlooked in the construction phase and commitments dating back to 1999 remain unfulfilled. They still believe in ‘their’ mine and mourn the loss of the partnership that existed at the time of the relocation of San Cristobal.

- In October 2005, a contractor opens a road though community gardens outside of the agreed area of construction operations. For the community of Culpina K this is an illegal act. Community relations collapse for a period with demonstrations and confrontation with the company. MSC are able to negotiate a letter agreement that allows work to continue and begins a protracted process of negotiation for the acquisition of additional land for mine infrastructure facilities. Culpina K remains at a distance due to rising concerns that they will be adversely affected by the tailings facility.

Phase V – Late 2006 – Present Day: Rebuilding the Relationship

- In October, 2006, management comes to recognize the problems and risks created by the damaged relationship and takes action to improve the situation. The company proposes the formation of a community based process for the design and management of community development programs. This action re-legitimizes the company as the communities see it as both an act of respect and an opportunity to take control of their own future. At the same time MSC begins an accelerated program to comply with all prior commitments. The communities start to see progress and feel reassured. Construction ends, training and full time employment is available to all. Dialogue is established with Culpina K around management of the tailings. Legitimacy strengthens.

- In 2007 a management team is appointed to run the mine, replacing the construction team, which brings stability and quickly establishes a positive dialog with the communities. All prior commitments have been met or are in a visible process of being met. An accelerated local employment program is initiated. Community based planning for social and economic development is underway. Credibility is restored.

- MSC responds to community concerns regarding the management of tailings by forming a joint monitoring committee with the community. Essential infrastructure improvements are made in San Cristobal and Culpina K. Credibility is strengthened. As ‘co-owners’ of the mine, the communities make representations to the national government in support of the company in response to statements of increased taxes and threats of ‘nationalization’. However, trust remains elusive.

- By late 2008, with the mine in operation and the communities fully involved in the management of their own development in collaboration with MSC and local and regional government. There are early indications that trust could return to the relationship.

A formal survey of perceptions in November, 2009, revealed that the quality of the SLO had changed very little from the situation in late 2008. It appears that the relationship with the communities in the immediate impact area of the San Cristobal Mine has stabilized and, with continued attention, the SLO can now be maintained at or close to the level of approval.