What Is the Social License?

The Social License has been defined as existing when a project has the ongoing approval within the local community and other stakeholders, ongoing approval or broad social acceptance and, most frequently, as ongoing acceptance.

At the level of an individual project the Social License is rooted in the beliefs, perceptions and opinions held by the local population and other stakeholders about the project. It is therefore granted by the community. It is also intangible, unless effort is made to measure these beliefs, opinions and perceptions. Finally, it is dynamic and non-permanent because beliefs, opinions and perceptions are subject to change as new information is acquired. Hence the Social License has to be earned and then maintained.

The differentiation into approval (having favorable regard, agreeing to, or being pleased with) and acceptance (disposition to tolerate, agree or consent to) can be shown to be real and indicative of two levels of the Social License; a lower level of acceptance and a higher level of approval. While the lower level is sufficient to allow a project to proceed and enjoy a quiet relationship with its neighbors, the higher level is more beneficial for all concerned.

On occasions, the Social License can transcend approval when a substantial portion of the community and other stakeholders incorporate the project into their collective identity. At this level of relationship it is not uncommon for the community to become advocates or defenders of the project since they consider themselves to be co-owners and emotionally vested in the future of the project, such is the strength of self-identification.

The concept of an informal ‘social’ license is comfortably compatible with legal norms in countries that operate under the principles of common law. However, the concept runs into difficulties in countries such as those in Latin America that operate under the principles of civil law, whereby only an official authority can grant a ‘license’. As a consequence, while communities and civil society are eager to see the social license in terms of a dynamic, ongoing relationship between the company and its stakeholders, regulators (and in turn many companies) see the ‘license’ in terms of a formal permission linked to specific tasks and events in which the regulator plays the central role in granting the ‘license’.

Gaining and Granting the Social License

A social license is usually granted on a site-specific basis. Hence a company may have a social license for one operation but not for another. Furthermore, the more expansive the social, economic and environmental impacts of a project, the more difficult it becomes to get the social license. For example, an independent fisherman who is member of an indigenous group will normally get an automatic social license from his community. A mining company wanting to relocate an entire village faces a much bigger challenge.

The license is granted by “the community”. In most cases, it is more accurate to describe the granting entity as a “network of stakeholders” instead of a community. Calling it a network makes salient the participation of groups or organizations that might not be part of a geographic community. Calling them stakeholders means the network includes groups and organizations that are either affected by the operation or that can affect the operation. For example, ranchers that would have to accept a land swap involving part of their pasture land would be affected by a proposed mining operation, without having much affect on it, provided they accepted the deal. By contrast, a para-military group of insurgents, or an international environmental group, that might attack the project site, each in their own way, would have effects on the operation, without being affected much by it. They would be stakeholders too.

The requirement that the license be a sentiment shared across a whole network of groups and individuals introduces considerable complexity into the process. It begs the question whether a community or stakeholder network even exists. If one exists, how capable is it of reaching a consensus? What are the prerequisites a community or stakeholder network must have before it becomes politically capable of granting a social license? These complexities make it more difficult to know when a social license has truly been earned.

What makes up the Social License?

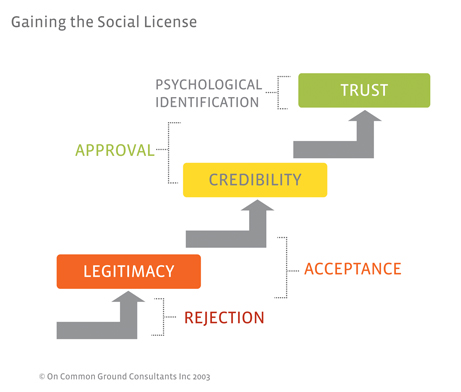

More than fifteen years of accumulated research and experience has allowed recognition that the normative components Social License comprise the community/stakeholder perceptions of the social legitimacy and credibility of the project, and the presence or absence of true trust. These elements are acquired sequentially and are cumulative in building towards the Social License. The project must be seen as legitimate before credibility is of value and both must be in place before meaningful trust can develop.

In practice, the absence of legitimacy leads to rejection of a project, the presence of legitimacy and credibility leads to acceptance of a project while a high level of credibility and the presence of trust is the basis for approval. The most significant level of Social License, co-ownership, can only occur when a high level of trust is present.

In more detail the normative components are:

- Social Legitimacy: Social legitimacy is based on established norms, the norms of the community, that may be legal, social and cultural and both formal and informal in nature. Companies must know and understand the norms of the community and be able to work with them as they represent the local ‘rules of the game’. Failure to do so risks rejection. In practice, the initial basis for social legitimacy comes from engagement with all members of the community and providing information on the project, the company and what may happen in the future and then answering any and all questions.

- Credibility: The capacity to be credible is largely created by consistently providing true and clear information and by complying with any and all commitments made to the community. Credibility is often best established and maintained through the application of formal agreements where the rules, roles and responsibilities of the company and the community are negotiated, defined and consolidated. Such a framework helps manage expectations and reduces the risk losing credibility by being perceived as in breach of promises made, a situation common where relationships have not been properly defined. A tip to company people – avoid making verbal commitments since, in the absence of a permanent record, these are always open to reinterpretation at a later date.

- Trust: Trust, or the willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another, is a very high quality of relationship and one that takes both time and effort to create. True trust comes from shared experiences. The challenge for the company is to go beyond transactions with the community and create opportunities to collaborate, work together and generate the shared experiences within which trust can grow.

What are the principal challenges to gaining the Social License?

As indicated above, there is often considerable complexity involved in gaining and maintaining a Social License but, properly prepared and supported, the challenges created by such circumstance can usually be overcome. Difficulties arise most frequently when companies are unable or unwilling to make the nominal investment to make things work. The most common problems encountered in our experience are:

- The company sees gaining a Social License in terms of a series of tasks or transactions (in effect making a deal), while the community grants the License on the basis of the quality of the relationship – a cultural mismatch that risks failure.

- The company confuses

- Acceptance for Approval

- Co-operation for Trust

- Technical Credibility with Social Credibility

- The company

- Fails to understand the local community (Social Profile) and the local ‘rules of the game’ and so is unable to establish social legitimacy

- Delays stakeholder engagement

- Fails to allocate sufficient time for relationship building

- Undermines its own credibility by failing to give reliable information or, more commonly, failing to deliver on promises made to the community.

- Fails to respect and listen to the community

- Under-estimates the time and effort required to gain a SLO

- Over-estimates (or, worse, assumes) the quality of the relationship with the community

Can the community fail to grant the License?

Yes, the term ‘community’ is frequently used in a way that suggests a singleness and purpose that does not always exist. Most ‘communities’ are really aggregations of communities, kinships or interest groups that operate as a network. However, the concept of the Social License to Operate presupposes that all of the families, clans, interest groups and institutions in a geographic area have arrived at a shared vision and attitude towards a resource development project. This kind of cohesion is often absent, and therefore may have to be built. That is why earning a Social License to Operate often involves building social capital in a process that is also known as ‘community building’, ‘capacity building’ and ‘institutional strengthening’, among others.

The key to a community’s capacity to issue a meaningful Social License is the pattern of social capital it has in its network structure. Without the right patterns of social capital within the community and between the project and the various elements of the community network, it is difficult, if not impossible, to gain and retain a Social License to Operate.

Companies that want Social License need to know the patterns of social capital in the network they wish to interact with. With this information, the company knows where to place effort. However, one size does not fit all. Each community has its own specific issues and interests that can form the basis for relationship building between the company and the community, and can create social capital and, in turn, the Social License –An early requirement is therefore the need for the company to undertake social studies to map and understand the social structure, issues and vision of the various individuals, groups and organizations in the network that collectively form the ‘community’.

Can you measure the Social License?

Yes, a survey instrumet, ‘SociaLicense™’, has been developed that uses a number of indicators to measure the level of Social License that exists at any one time in terms of Rejection, Acceptance, Approval and Co-ownership. However, it is important to remember that the quality of the Social License is dynamic and responsive to changes in perceptions regarding the company and the project and is also susceptible to outside influences; it therefore has to be maintained. To be confident as to the status of a Social License, it should be measured periodically and the results of the survey used to modify practice with the intention of improving the quality of the relationship between the project and the community/stakeholders.